There are two sides of the same coin, and this is especially true when it comes to referencing. I know you are wondering – how on earth can a reference have two sides? What I am actually referring to is the act of referencing or substantiating a job. In Ireland it is outlined in both SI.541 and the IPHA Code of Practice v8.5, clause 4.3, and Medicines for Ireland Code of Practice clause 4.4, promotional material must be up to date, verifiable, and accurately reflect current knowledge and opinion. It also must be accurate, fair and balanced and the information capable of substantiation. This is also covered under the ABPI code in clause 14 code, which specifies that clear references must be given when promotional material refers to published studies. When we are creating and approving materials we need to ensure that what we are saying and putting out there is accurate and verifiable whether it is a marketing claim or medical education or disease awareness, and one of the best ways to do this is by having those references available for checking during the material approval process. Ultimately, we are focusing on patient safety and therefore we need to make sure we can back up what we mean with a trusted source.

There are a few things to consider when referencing a material

(1) The veracity of the claim and how up to date and reliable your source is

(2) The ability and ease with which the reviewer can confirm the reference is the right one

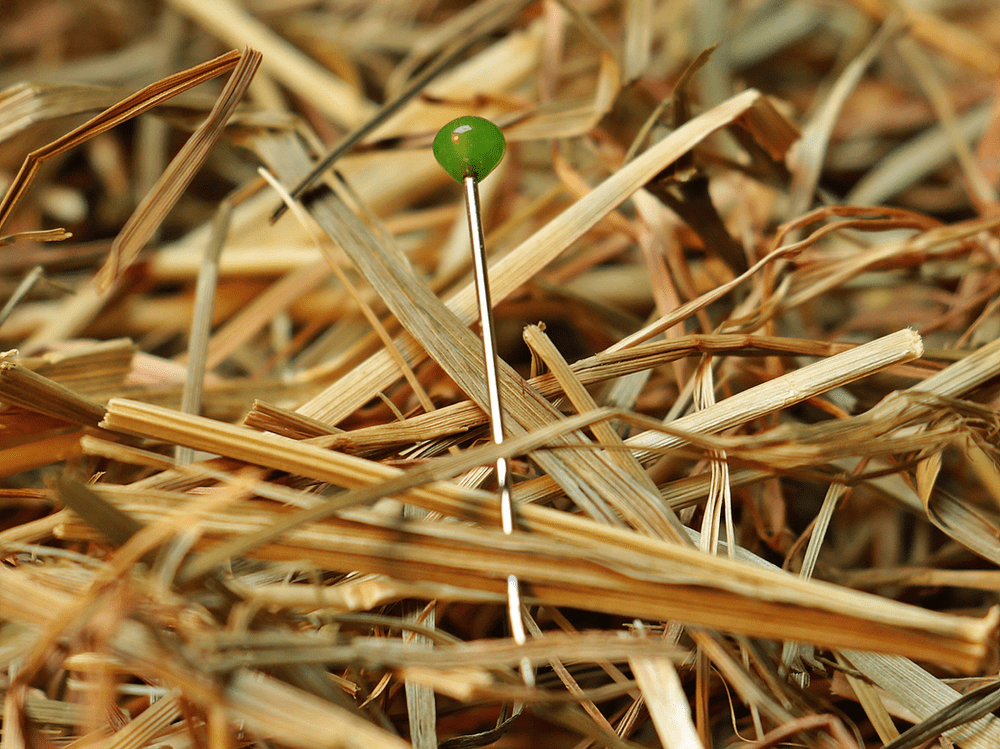

If you are an originator of material I’m guessing the task you least relish is marking up the relevant section of the reference, and, if the function is available (thank you PromoMats), anchoring them to the relevant section of the text. I hear you, I really do, I have been that soldier and it is time consuming, but it is worth it. Why? On the other side of the coin, you have your reviewers who are looking at your claims and information and trying to match what is in the reference to what you are saying. If you are reviewing a piece and it is properly marked up and linked, you can smoothly and expediently work your way through the review (depending on the size of the material). If however, there is just a paper attached or the word results highlighted in the abstract for example it is at best, like pin the tail on the donkey, and, at worst, finding a needle in a haystack trying to locate the right piece of information you think the originator means to substantiate the claim. The knock-on effect of this is that a reviewer can spend an inordinate amount of time trying to locate the right information, which may or may not be in the reference. This in itself delays the review process, as if the reviewer can’t locate it then it will land back on the originators desk, necessitating a further round of review and most likely a request that the references are marked up and anchored correctly. Not so bad if it is a short one pager but if it is 4 page meeting report or deck with 30 slides (or more) it takes a lot more time. Over the years I would say the main reason pieces get returned to the originator is incorrect referencing.

Wait, you say, but I did send on a piece with marked up references, or at least the agency did, so why am I still having the piece that sent back with queries on references? There could be several reasons for this:

1. The incorrect section is highlighted within the reference, and it doesn’t actually support what is stated in your piece.

2. All the references were anchored to the last page of your material and your reviewer is playing hunt the needle trying to find which reference goes to which piece of information.

3. The anchor is linked to the word “Results” or a piece in the abstract. The abstract is just a summary and doesn’t actually provide the evidence to support the claim – that is within the body of the paper itself. Go to the main body of the paper – always.

4. It’s not the most up to date reference. You would be surprised how often this happens. A red flag for a reviewer is if an abstract or a

poster more than a year old is quoted as reference. Go back and check if it has been published as a paper, the results may have changed slightly and the published paper always trumps the abstract (or data on file). There is a hierarchy of evidence which should be utilised when referencing.

5. It’s not in English (I’m only half joking here, I have received jobs with references in different languages – it happened to be one I speak, but by and large I wouldn’t bank on your reviewer being a polyglot).

The net result of the above is that the material goes back to the originator and they, or the agency who referenced the piece, have to go back and redo the work of referencing, which is both time consuming and costly. Not to mention a further round of review, which can impact on your timelines. If you as an originator, or your referencing agency, can’t find the relevant piece within the reference, then it is highly unlikely that the reviewer, who isn’t as close to the material is going to be able to locate it.

So how to fly through the review process and minimise the number of rounds needed:

Best practice tips

1. Make sure you have the most up to date publication with your data (a quick pubmed search will normally help).

2. Find the relevant sentences/figures within the body of your reference and anchor it to the relevant section within the material.

3. Do this for each individual claim, set of numbers, data within a piece.

4. For webpage links, always make sure they are up to date and the last accessed date is within the approval timeline

By taking this approach the reviewer can click on the link(s), compare the two and move swiftly to the next piece of information. Make sure to share the tips with whomever is referencing your materials. You would be surprised at the positive impact this will have on your material approval timelines (and your budget).